That pound of flesh again… | Joe Friggieri

There is a Shylock and an Antonio in all of us, as theatre director and philosophy professor Joe Friggieri explains about his forthcoming production of The Merchant of Venice at San Anton

“Hath not a Jew eyes? Hath not a Jew hands, organs, dimensions, senses, affections, passions; fed with the same food, hurt with the same weapons, subject to the same diseases, healed by the same means, warmed and cooled by the same winter and summer as a Christian is? If you prick us do we not bleed? If you tickle us do we not laugh? If you poison us do we not die? And if you wrong us shall we not revenge?”

Even those totally unfamiliar with the works of William Shakespeare may well recognise those lines, though they may not know the play that made them famous.

They have after all reverberated across the world stage for the past 400 years; and besides, the words immortalised by Shylock in distant 1596 seem to resonate with a contemporary relevance that stretches far beyond the confines of the Renaissance Venice for which they were first conceived.

They also seem to transcend the immediate anti-Semitism that the play itself sets out to address. Almost half a millennium later we are still talking about racial prejudice in terms that are – barring the differences in linguistic expression – intrinsically Shakespearian.

Then as now, we are consistently confronted and to a point challenged by a sense of ‘otherness’ – be it in relation to a migrant population of different race or skin colour, or even adherents of other political or social groupings – and the sentiments that accompany such confrontations remain virtually indistinguishable from the racist taunts endured by one of Shakespeare’s most ambiguous stage villains.

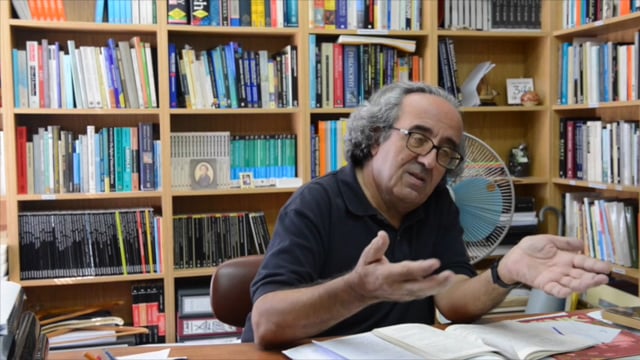

It is perhaps for this reason that Shylock’s speech – even when read out quietly by mild-mannered academic Joe Friggieri in the comfort of his University office – seems to somehow speak to us with the same urgency and force today as when first performed by The King’s Men more than 400 years ago. And there are other aspects in which The Merchant of Venice seems altogether more contemporary than other Shakespeare plays… even more famous ones such as Hamlet or Macbeth.

Ultimately, the tale is one most will be able to relate to for a host of other reasons apart from its racial overtones. It also involves usury and debt – two issues that are still of great relevance to the Maltese social and political milieu today – and for all sorts of reasons, a modern audience will surely empathise with the dilemma faced by Antonio (the merchant who gives the play its name) when borrowing money from a man he detests and has publicly reviled at every opportunity, only to find that he cannot pay him back.

Simmering beneath the surface is another theme of great contemporary relevance: justice. Again, many will surely recognise the character trait for which the Jewish moneylender Shylock has since become famous, and has even contributed an expression to the English language.

Shylock’s insistence on a ‘pound of flesh’ as repayment for Antonio’s debt has since been entrenched in popular parlance as a metaphor for the unreasonable insistence on the letter of the law at the expense of its spirit. It is the same punctilious, inflexible and obstinate attitude that also gives us the Maltese expression, “tal-punt”.

Joe Friggieri, professor of philosophy at the University of Malta is directing The Merchant of Venice for this year’s MADC summer appointment with Shakespeare. It seems appropriate, then, to ask him if the choice of play was in any way dictated by its apparent relevance to Malta’s own simmering racial tensions… and if so, how he intends to approach this relevance in his role as theatre director.

“I would say The Merchant of Venice has particular relevance in connection with two main themes: the first is racial prejudice, and the second, the creation of permanent minorities as a result of social exclusion,” Friggieri begins after reading me through the most pivotal speeches and scenes.

“In the play, Shylock is hated because he is a Jew. I think there is a lot of prejudice among us, in Malta, based simply on the fact that there are people who come from other countries – we call them ‘immigrants’ – who are different from us. They have a different race, a different religion, a different culture… and of course the colour of their skin is also different.

"I find that there is a lot of prejudice based simply on this very simple fact: that people who come here from Africa are black. This play deals with this kind of problem, but obviously in the context of anti-Semitism, which was rampant in Shakespeare’s day… and unfortunately, it is a monster that is raising its head again. Not so much perhaps in Malta, but certainly in other parts of Europe.”

From this perspective the play’s relevance goes beyond the purely local concerns with racism. It must also be seen against a wider backdrop of the resurgence of political racism elsewhere in Europe and the world… and this entails what Friggieri describes as a ‘particular responsibility’ for anyone who approaches the text with a view to performing it on the stage.

“After the holocaust and the atrocities of the Nazi regime, and with the anti-Semitic monster raising its ugly head again, those taking part in producing or discussing The Merchant of Venice must show the dangers of all kinds of racial prejudice,” Friggieri observes. “One must present it in a way that makes sure the audience doesn’t read it as an anti-Semitic play.”

At the same time, however, The Merchant of Venice has often been criticised precisely for its perceived anti-Semitism. It is by no means universally accepted that the play actually condemns the racism meted out to Shylock the Jew – a highly versatile role, by the way, which has been performed (to considerably different effect) by such actors as Lawrence Olivier, Patrick Stewart, Al Pacino… and now Manuel Cauchi.

Shakespeare’s own views on this subject are at best ambivalent, and the play’s ethos seems to be pulled in different directions. Shylock is accorded by far the best lines in the play, and it is difficult to come away from the trial scene unmoved.

Clearly, we are invited to sympathise with him as a victim of prejudice. Yet the resolution of the play itself works heavily against the Jew and in favour of the man who insulted and demeaned him… and at the very climax, Shakespeare seems to go out of his way to rub in a Christian ethos (even insisting that Shylock convert to Christianity, for instance) that reeks of self-righteousness.

How does Joe Friggieri interpret this apparent ambivalence as a director, and – at the risk of giving too much away – how does his own production reflect this interpretation?

“We should be careful not to attribute to Shakespeare the prejudices of some of his characters. On more than one occasion he makes it quite clear that his sympathies lie with Shylock. Not in all the scenes, naturally. One can argue about that: one can discuss the impact of the final scene at great length. But I feel that that in the famous ‘Hath not a Jew eyes?’ speech, we are meant by Shakespeare to be on Shylock’s side… and not on the side of his persecutors, the Christians.”

Friggieri adds that there are other memorable instances in the play where Shylock cannot fail to win the audience over. In his very first appearance in Act One Scene Three – the first time we see Shylock -he reminds Antonio of the insults he has received simply because of his race: He has been called misbeliever, cut-throat dog, spat upon and kicked like ‘a stranger cur’.

“And he has put up with it ‘with a patient shrug, for sufferance is the badge of all our tribe’,” Friggieri points out, pausing to read out the speech in full. “I think that’s very beautiful… [the scene] also makes the point very clearly, and I think the audience will understand what Shylock was trying to tell Antonio…”

Whether Antonio understood it, however, is another question.

“Antonio’s reaction is certainly not that of an exemplary Christian. He replies by saying that he will spit on him again, call him dog and kick him, even if Shylock lends him the money he needs…”

Nor is anti-Semitism the only incidence of racism to make itself felt in The Merchant of Venice. There is also a sub-plot in which Portia – the beautiful, intelligent and wealthy heroine (played by Coryse Borg) who ultimately dispenses ‘justice’ to Shylock and Antonio while disguised as a male judge – must fend off the advances of a number of suitors so that she can marry the man of her own choice, Bassanio.

Among the suitors is the Prince of Morocco, who is marked from the rest even at a glance by his skin colour alone. Admittedly the African prince is accorded far more respect in the play than the hated Jew… but again, the Christian heroine proves incapable of looking beyond the superficial, and expresses naked relief when he fails the marriage test devised by Portia’s father, and chooses the wrong casket.

Friggieri however cautions against reading too much of Shakespeare’s own opinions into the lines uttered by one of his characters (an important character, no doubt, but still a lone voice among several).

“In Portia’s first scene with the Prince of Morocco, the prince speaks proudly of his dark skin as ‘the shadow’s livery of the burnish’d sun’. He carries himself with great dignity, and confronts Portia with a powerful argument against prejudice. It is her attitude, not Shakespeare’s, that we find irritating, based as it is on her dislike for the colour of Morocco’s skin. ‘Let all of his complexion choose me so,’ she says…”

You can almost feel Portia’s sigh of relief in that single line. And few can deny it is a sense of relief that would be shared by many in a similar predicament today.

But back to Shylock. “There is no doubt that Shylock’s role is based on anti-Semitic stereotypes, and that he is portrayed as a villain,” Friggieri concedes. But this in itself, he argues, does not make The Merchant of Venice an anti-Semitic play.

“We may still see Shylock as a vengeful individual without seeing him in this respect as a representative of his race. Even more importantly – and this is what I try to show in my production – what Shylock says and does brings out the hypocrisy of false Christians.

His words and actions are an indictment of their attitude, revealing contradictions between what they preach and how they behave. Shylock is only following their example when he demands his pound of flesh. ‘The villainy you teach me I will execute, and it shall go hard, but I will better the instruction…’.”

And because Shakespeare knew a thing or two about how to write plays, the resulting courtroom drama is tense and compelling by any standard. Clearly he uses his stagecraft to maximise the audience’s sympathy towards Shylock, even when turning the knife in with an unreasonably cruel final verdict.

“At the trial Shylock is the object of hostility from everyone on stage. When sentence is passed, he is allowed to escape with his life only on condition that he become a Christian. And it’s a terrible condition.

It is nothing but the imposition of the will of a Christian majority on a non-Christian ‘alien’… and a modern audience will almost certainly react to this part of the sentence with disgust. They should. And how does a director do that? Just by simply underlying, highlighting and emphasising how Shylock reacts to that sentence. He is completely destroyed…”

This is, in Friggieri’s view, a case of “the majority (in this case, Venetian Christians) imposing an unjust sentence, a terrible sentence, on a minority…”

All in all, then, Shakespeare enthusiasts are in for a more politically and socially charged theatrical experience than is normally associated with the Bard of Avon’s lighter comedies. And this in turn points towards another extraordinary reality underpinning this year’s performance.

Shakespeare productions are notoriously difficult (and expensive) to put up because they tend to involve a large cast and require considerable input from the costume, stage design, lighting, etc, point of view. And that’s not even going into the quality of production, which also needs quality acting across the full dramatis personae.

Yet MADC, an amateur company, has been producing successful Shakespeare productions every summer since the 1930s, in a country where theatre is often perceived as a money-losing indulgence.

“Yes, there are difficulties,” Friggieri – who has directed several of the MADC’s summer Shakespeare plays, even though this is his first stab at the Merchant – admits. “In my view there are three reasons for the MADC’s success.

First, the plays themselves. Shakespeare is such a great dramatist that his works continue to exert a kind of magnetic pull on different age groups, for different reasons. Secondly, the quality of the productions. Of course, this varies from play to play, but over the years MADC has succeeded in roping in the best actors and a long line of experienced theatre directors to work for them.

Last but not least, the venue. San Anton Gardens offer the ideal setting for large productions like Shakespeare. The performance space is beautifully ‘backdropped’ by trees on one side and the palace on the other. It is, for this reason, extremely flexible and directors can choose which way to set their production. Apart from that, the Gardens at night create a magic atmosphere that is quite unique. There is no other venue on the island that offers theatre audiences that kind of experience.”

The Merchant of Venice will be running from Wednesday 23 to Wednesday, 30 July at San Anton Gardens, Attard

.jpg)