What’s in a game?

A group of researchers from the newly inaugurated Institute for Digital Games at the University of Malta are working hard to integrate video games into the educational scenario… and it seems as though they’ve got the authorities on their side. Teodor Reljic speaks to Rilla Khaled and Giorgios N. Yannakakis about their work with the Institute.

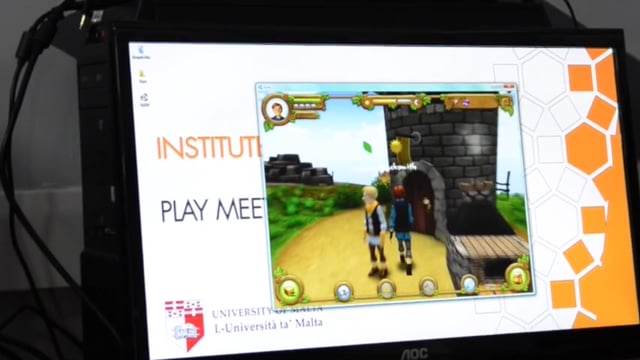

Officially inaugurated last month, the University of Malta’s Institute for Digital Games has been playing host to an exciting educational initiative – the creation of a community-based video game, ‘Village Voices’, which is aimed to foster a spirit of conflict resolution in younger players.

Created under the auspices of an EU project – the ‘SIREN’ initiative – Village Voices was made possible through the efforts of researchers Rilla Khaled and Giorgios N. Yannakakis, who both form part of the Institute for Digital Games and are currently working to develop additional games which could also be used in an educational context.

‘Village Voices’ challenges players to work together to ensure that a community runs smoothly – taking care of amassing necessary natural resources, food and the like. Players are also given the option to behave selfishly – by stealing their fellow players’ items, for example – but the game’s in-built narrative will make it clear to the player that such actions aren’t worth it in the long run, and that working hand-in-hand ultimately results in a more satisfactory outcome.

The game’s ultimate aim is to teach children productive and healthy ways of dealing with conflict, and the team is keen to start introducing the game into classrooms on the island.

Though both Yannakakis and Khaled are well aware that video games still carry the stigma of being “mere entertainment” – and, arguably, even of being nothing more than a “waste of time” – it’s a challenge that they won’t be facing alone, as Education Minister Evarist Bartolo has made it clear that he is resolutely on their side.

Flagging the possibility of incorporating such games in schools with the help of the ‘One Tablet Per Child’ electoral pledge – which, as its name suggests, will endeavour to equip all young pupils with digital tablets for school use ¬– Bartolo said that Malta should take advantage of the rise of the digital gaming industry within its shores, especially for educational purposes.

“We are in a situation right now in Malta where we have a nascent digital game industry. This is a splendid opportunity and it would be foolish not to exploit it,” Bartolo said, adding that any challenges related to this move would have less to do with technology and is more a matter of “societal and psychological” factors.

“There are many adults who look down on games as a waste of time, and they need to be convinced. We also need to equip our teachers with the necessary professional competencies to embed digital games in the teaching and learning experiences,” Bartolo added.

Yannakakis isn’t concerned about the available technology either as, tablet or not, the games that he’s working on with his team require little more than “a good internet connection and a moderate-speed computer” to run.

Mentioning in-development games like iLearn2 (which focuses on dyslexia), Yannakakis says the games also take into account the overall context of the classroom.

“The pedagogical scenarios followed are already interwoven within the games we propose, and the interface allows the educator flexibility and control over the game content experienced – for instance, educators can design the game scenarios children will experience.”

Yannakakis’s colleague, Rilla Khaled emphasises the importance of the context in which the game is played, arguing that more or less any game could be made relevant in an educational scenario if the student is given the right reference points.

But this, of course, may bring further challenges.

Once again bringing up the knee-jerk suspicion to video games parents and teachers may initially have – “but this happens with every medium: people have been suspicious of books, film, and TV” – Khaled insists that “just having the game in the classroom doesn’t mean learning will magically happen”.

“Teachers need to know how to integrate specific games as teaching tools and what might be appropriate teaching strategies to pair with games to leverage learning. Decades of simulation game research has shown that the ‘debrief’ conversation held after a learning game greatly assists people in making sense of play experiences, being critical about them, and being able to connect them with life experiences.”

So what kind of ‘serious’, or ‘educational’ game would be the best fit for Malta at this point in time?

Bartolo suggests a fairly broad sweep – “Maltese culture, personal development, family relations.

“Then we can go into a more specific direction, such as our rich historical heritage, meeting the need of our ever-growing non-Maltese speaking population and literacy in the Maltese language, which is an important element in our recently launched ‘National Literacy Strategy for All’,” Bartolo added.

Whatever direction these games take, Khaled suggests that they may very easily end up reflecting the culture they’re created in, as the way a game works tends to be similar to the way we live our day to day lives.

“Just as in human cultures, cultural members learn to rely on cultural rules for survival and progression, within games, players learn to do the same. Cultural values and behaviours can be expressed through game mechanics, rules, scoring systems, and win/lose conditions.

"If we map games to cultures, we can view play as actions within a culture that supports and encourages particular sets of values and modes of behaviour, while discouraging, disallowing, and punishing others,” Khaled says.

.png)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)